Shortly after Ken Sims passed away, Jon Critchley scanned the series of articles by Ken that appeared in Just Jazz Magazine in 2004/5 and sent them to Fred Burnett at Jazz North West.

After converting the images into text and photographs, Fred sent them to me at Jazz&Jazz. With his help, I have pieced them together for this special feature.

Fred will place a link to the feature on Jazz North West.

So, in memory of Ken and courtesy of Jon, Fred, Jazz North West, and especially Just Jazz*, below are the condensed extracts from his series of Just Jazz Magazine articles: “A Muskrat’s Ramble”.

*Note: These extracts from Ken Sims memoirs were taken from his ‘Muskrat Rambles’ that featured in Just Jazz magazine in 2004/2005. I publish these extracts with kind permission of Just Jazz. Just Jazz tell me that it is hoped that one day his ‘Rambles’ could be put together in book form as they are excellently written and deserve greater recognition.

Peter M Butler

Editor & Proprietor Jazz&Jazz

*** *** ***

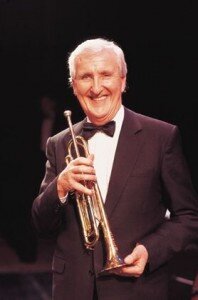

Ken Began: “Dad bought me a trumpet”

My interest in music was sparked by listening to my father (he who must not be disturbed) practising piano in the front room, the Radio Rhythm Club, Buddy Featherstonehaugh, Harry Parry etc, and a radio programme called ‘Housewives Choice; which frequently featured records by Harry Gold, Sid Phillips and, best of all, Fats Waller.

My early musical training was on piano. I had huge hands for a kid; I could span a tenth (ten notes) when I was eleven, but my heart wasn’t in it, the war was on and I had decided to join the Commandos. After all, the Germans had bombed our chippie and my dad’s pub. They’d asked for it.

My Dad, who had given up on me playing piano, said he would buy me a trumpet… The trumpet was silver plated and had the logo ‘Monarch’ and some numbers engraved on the bell. I thought it was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen.

Dad took me to see Nat Gonella at a music hall in Liverpool. I sat through comedians telling jokes I didn’t understand, a female contralto emitting

ear-piercing screeches, Irish tenors with quivering tonsils, performing dogs and acrobats… It seemed to go on forever. Then Nat came on, top of the bill! He only played two tunes, “Tiger Rag” and “The Saints”. No problem with practising now, in fact the opposite. “You’re not playing that trumpet until you have finished your homework” would come the cry from the real world.

My first paid gigs were with my Dad’s dance band. We played Old Time Dance, Modern Dance, Square Dance music, Swing and even a little jazz.

In the early fifties I worked in Chester where I was introduced into the mystical inner circles of the local jazz record club. Club meetings were held in a loft over the Chester Rowing Club, on the Dee. At that time, extensive record collections of New Orleans Jazz were, if they existed, rare. The idea was that members would take one of their treasured 78’s to the meeting, where it would be examined by the senior members. If found suitable, your record would be played on a wind-up gramophone and afterwards discussed in great detail and reverent tones. It was here that I first heard the music of Oliver, Armstrong, Morton, Kid Ory, Bunk, George Lewis and the blues singers.

They were a revelation. Well, fair do’s, trumpeters can’t hear what the audience hears. We are at the wrong end of the instrument.

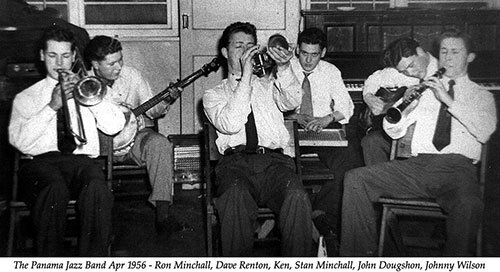

I joined the Panama Jazz Band which was playing in West Kirby, loosely in the George Lewis revival style, clarinettists John Wilson and Bruce Bakewell doing the hard work. That band was quite a family affair, containing, at times, the Minshall brothers and the Renton brothers. Dave Renton was then playing banjo. The last time I played with Laurie Renton was at The 100 Club where he played cornet just fine.

Aided and abetted by Gordon Vickers, I also joined the Muskrat Jazz Band.

Humph Out of London

Bands working out of London came and played at Preston Hall and the Pavilion Theatre including The Humphrey Lyttelton Band, with Wally and Bruce on clarinets. Humph’s leed was imperious and played with great style. I was very impressed. The Alex Welsh band came, a great Chicago-style band. He had a very good clarinet player, I think it was Archie Semple, who was a bit cramped for space on the ensembles. A lengthy drum solo with ‘ooowaagh, ooowaagh’ vocal break by Lennie Hastings, called The Battle Of Hastings climaxed the show.

The next concert was by the Ken Colyer Jazzmen. Shock, horror, no drummer. I can’t remember exactly who was in the band, but Bill Colyer was on washboard. The band demonstrated a complete lack of showmanship. Ken sometimes played with his back to the audience, a cardinal sin. He didn’t smile and hardly spoke. I thought they were terrific. The band developed an almost hypnotic swing and played superb, lengthy, ensemble jazz. Was this why Ken and Chris Barber parted company?

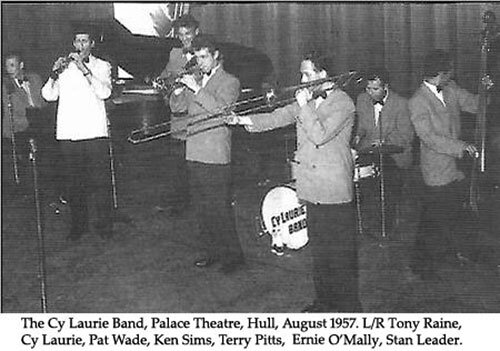

Shortly after the Colyer concert, a BBC broadcast, I think The Festival of Light Music, turned into a mini riot when the denizens of the Cy Laurie Club chanted, “We want Cy, we want Cy,” and booed all the other acts. I knew then that the revolution was really underway and that its centre was in London. For me, there were now three cult heroes. Humph, Ken and Cy.

Cy offered me a trial period with his band. Most of this period was spent on his farm in Essex, learning his collection of Oliver, Armstrong, Morton and Dodds records. After the trial period ended I got the job and was paid the princely sum of £12 per week. My bed-sit cost me £5 per week!

About this time, something quite extraordinary happened. Jazz fans, including a doctor’s son, Alan Sitner, somehow acquired possession of some old wine or stock cellars situated amongst the bomb sites that still littered Liverpool. A small army of jazz enthusiasts cleaned the place up and installed some basic facilities. They called it The Cavern. There was only one stairway in or out, the toilet facilities were totally inadequate and there was no mechanical ventilation. When it was packed, conditions could be appalling, what with the smoke, perspiration and cold walls. Oh, the romance of it all! Well, weren’t all the best jazz clubs in dimly lit, smoky, sweaty cellars? In the interval there were guitar bands, initially skiffle groups, then rhythm and blues bands. One of these became the Silver Beatles.

Cy’s club was in a cellar beneath the Panama Night Club in Great Windmill Street, London. Like The Cavern, there was one stairway for in and out, poor toilet facilities and no ventilation system. The Cavern had a vaulted brick ceiling. If I aimed my horn into it I could make some use of the acoustics. The ceiling was relatively low, as was the stage. When the club was full, it was like playing into a mattress. In the mid-fifties, most jazz clubs were not licensed, and whilst I could get a bottle of beer at Mac’s bar upstairs, I used to lose weight playing at Cy’s. I recorded a weight loss of 6 lb. over one all-night session. I was 20 years old, weighed 10 stone and stood over 6 feet tall in my brothel creepers. The loss of 6lbs was a serious blow to my ambition to have broad shoulders and muscles. In the morning I looked like a wet mop with ears.

Humph’s & The Ken Colyer Club

William ‘Diz’ Disley … an irreverent character of outstanding musical ability, decided to broaden my horizons and introduced me to the doorman at Humph’s club and the Ken Colyer Club, and, most importantly, to the Star restaurant. The Star was run by two Greek Cypriot brothers who permitted gentlemen of fluctuating financial fortune the luxury of meals on tic. Consequently, it was a meeting place for musicians. I liked the place. You could sit around all day drinking tea, have a meal, chat to the boys from other bands and analyse the current rumours. Late at night we would be turfed out by Andreas with his plaintive cry of, “Ain’t you got no ‘omes to go to?”

Around March, Diz moved on and was replaced by Pat Wade (Brown). Pat was a guitar player who found that the typical 4-string banjo inhibited his style. Cy suggested he got a 6-string banjo which he could tune like a guitar. To our amazement he succeeded. For the benefit of the non-technical types, I should explain that 6-string banjos are almost as plentiful as rocking-horse poo. According to discographer Gerard Bielderman, the band recorded four tracks for Esquire on the 7 May, 1957. They were “South Rampart Street Parade”, “St. Louis Blues”, “St. Philip Street Breakdown” and “Burgundy Street Blues”. I have no recollection of the session whatsoever.

Well, at least one member of the audience was a jazz fan: a young trumpeter named Chez Chesterman was out there. Late summer of 1957 saw the band back in the recording studios, this time for Melodisc. We recorded nine tracks. “The Lonesome Blues”, “You Made Me Love You”, “Dippermouth Blues”, “Cootie Stomp”, “Weeping”and “Bow Tie Breakdown” (clarinet solos), “Old Miss Rag”, “Memphis Shake” and “Froggie Moore Rag”.

“To pick up gigs you had to be seen and if possible, heard.”

Telephones were thin on the ground then, so I was a regular at the clubs in and around Soho. Adjacent to, or within an area bounded by, Oxford St., Regent St., Shaftesbury Avenue and Charing Cross Road, there was the Humphrey Lyttelton Club, the Cy Laurie Club, the Ken Colyer Club, The Marquee, The Skiffle Cellar and various drinking (rhythm) clubs such as the A&A and the Nucleus Club, where you could get a drink and/or a blow. If I wasn’t there, I had just left or was on the way. Ken Colyer heard of my predicament, probably from Johnny Bastable, and in that soft voice and strange accent of his said, “Weel moan, you’d better come and stagy with me.” He had a charlady who used to do for him and cook him enormous meals. As soon as she had left the room he’d dump half of his meal on my plate. As I was starving I thought this was a wonderful idea. Then he got sick and booked me to dep for him.

He had a wonderful band with Mac Duncan (trombone), Ian Wheeler (clarinet), Colin Bowden (drums), John Bastable (banjo) and, I think, Ron Ward on bass. Mind you, when you play in front of Colin’s bass drum, it doesn’t much matter who’s on bass. Playing ensemble choruses with these guys was as easy as falling out of bed.

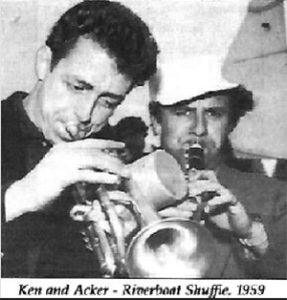

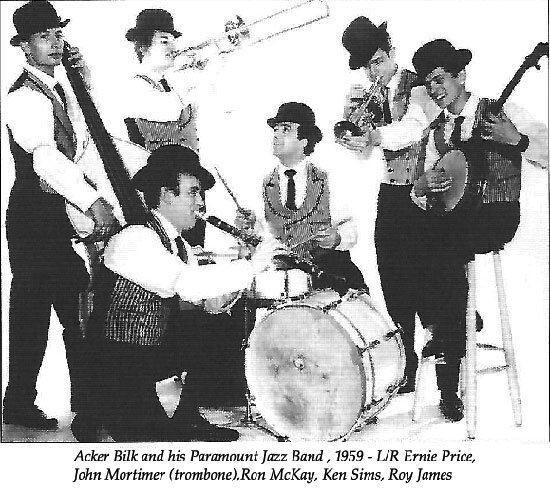

Acker Bilk

Acker’s band had just returned from Germany and they were having a hard time; in fact most of them lived in the attic above Alan Gatwood’s paper factory in Plaistow. In February, 1958, I went to see Acker’s band play at Humph’s club and had a sit-in. I stood in between Acker and his trumpeter, Bob Wallis, and noticed that Bob had filed the rim of his mouthpiece flat. It must have been like blowing on barbed wire. After one number, Acker asked me what I was doing. I replied, “Starving.” He asked me if I would like to join the band. I stifled a scream and nodded. Acker then leaned across the front of me and said, “Bob, you’re fired.” I was horrified, shocked, appalled. I said, “Can I have a sub?” The band was signed by the Lyn Dutton Agency; we were paid £15 per week and a share of the profits. Oh joy, I’d got a rise, my new flat still cost £5 per week so I now had more than £1 per day to spend. We were paid on Thursday. I was broke on Monday.

if I would like to join the band. I stifled a scream and nodded. Acker then leaned across the front of me and said, “Bob, you’re fired.” I was horrified, shocked, appalled. I said, “Can I have a sub?” The band was signed by the Lyn Dutton Agency; we were paid £15 per week and a share of the profits. Oh joy, I’d got a rise, my new flat still cost £5 per week so I now had more than £1 per day to spend. We were paid on Thursday. I was broke on Monday.

The band had Johnny Mortimer on trombone, Ernie Price on bass and Ron McKay on drums.

The record, “Mr. Acker Bilk Requests”, was sold out in five days and went into the Jazz Best Sellers list. The band was working seven days a week, and the money was going up. Sometimes I was still solvent on Tuesdays but I did not like the uniforms. They were all right for record covers, a bit of a laugh, perhaps, but they were now being specified in contracts. I discussed the situation with Diz Disley and Lennie Hastings over a cuppa in The Star. I said that I couldn’t imagine Ken Colyer or Humph wearing that gear on stage. Diz was of the opinion that Louis Armstrong would, and it wouldn’t make one note difference to him. Lennie agreed, so that was that. I tried to look on the bright side. The waistcoat had pockets for my fags and lighter, and the bowler made a nice mute. I still think we looked like plumbers in a flower garden.

The June, 1958, Floating Festival of Jazz was memorable. The sun shone and I was able to fill my lungs with clean sea air. We sailed to Margate on the ‘Royal Sovereign; where the bands were to swap boats for the journey back. We came back on the ‘Royal Daffodil’ with 3,000 people. Chris Barber missed the boat and we finished up with Ian Wheeler, Mac Duncan and Stan Greig sitting in with us. The audience loved it; so did I. Shortly afterwards the band toured Scotland. It was the band’s first tour outside of the London jazz scene. It was a big deal. Acker took his wife, Jean, (Ginger) and Ron McKay took his Danish wife, Liza. This was an event not to be missed. Acker taught me to tickle trout and we played to an audience of 2,500 at the Edinburgh Festival. We closed that tour at The Cavern Club where I introduced the lads from the Muskrats. There was some ale supped that night.

There were some wonderful trumpet/clarinet teams about then, but I thought that Acker and I were as good a team as any of them, and I still do. He seemed to know what I was going to play before I did, and we could do the Oliver/Armstrong break trick easy-peasy.

Slow Drag

By January, 1959, the Musicians’ Union had joined the human race and the George Lewis Band came to England. I was at Euston Station with members of the Ken Colyer Band and other musicians to welcome them. The place was packed. They were the last people to get off the train. A black face appeared at a door window, a huge roar went up, the face vanished. Several minutes later, a face appeared at the window and disappeared as the roof of a shed opposite collapsed under the weight of people on it. Eventually, Ian Wheeler’s lady, Maria, went into the train and emerged with Slow Drag’s bass. She was followed by Slow Drag, to applause, and then by the rest of the band.

On January 11, 1959, we were back in the Nixa Studios to record some Bilk vocals and recorded “Lump In The Line”, “Higher Ground”, “Carry Me Back”, and “”Louisian-i-a. It was called “Acker Bilk Sings” and went straight into the jazz best sellers chart. That night we went to the Odeon theatre in Tottenham Court Road to hear the George Lewis Band, first and second houses. The first house, first set, first number, George stamps his foot once and the band comes in – too fast. Surely our gods can’t be nervous? After a few numbers the band settled down. I have never been so excited by a band in my life, not before or since. They were out of sight.

On the 17 February, 1959, Acker recorded ‘The Noble Art of Acker Bilk’. The album made No. 1 in the jazz best sellers chart.

Louis Armstrong

In March, Louis Armstrong and his All Stars arrived in England. Because of work commitments I couldn’t get to see him in London. During his tour we had one day off. Keith Lightbody got it all sorted and we, together with Ernie Price and Johnny Mortimer, went up to Birmingham to see the man. “Sleepy Time Down South” put me in a trance. “Good evening everybody,” were the last words he said that I understood. If he had then said, “Thanks for coming to see me, goodnight,” the journey would have been worth it. I had seen the man who recorded “Cornet Chop Suey”, “West End”, “Sweethearts”, and all that stuff. Instead, he stepped away from the vocal mike, the only mike on the stage, raised his horn and blew a note that touched my soul. The quality of tone was such that it completely filled the theatre and probably the pub next door. I put my hands up to my face and locked my fingers against my forehead so no-one could see I was crying. In the interval, Johnny said, “What did you think of that?” “Not bad,” I said.

In March, Louis Armstrong and his All Stars arrived in England. Because of work commitments I couldn’t get to see him in London. During his tour we had one day off. Keith Lightbody got it all sorted and we, together with Ernie Price and Johnny Mortimer, went up to Birmingham to see the man. “Sleepy Time Down South” put me in a trance. “Good evening everybody,” were the last words he said that I understood. If he had then said, “Thanks for coming to see me, goodnight,” the journey would have been worth it. I had seen the man who recorded “Cornet Chop Suey”, “West End”, “Sweethearts”, and all that stuff. Instead, he stepped away from the vocal mike, the only mike on the stage, raised his horn and blew a note that touched my soul. The quality of tone was such that it completely filled the theatre and probably the pub next door. I put my hands up to my face and locked my fingers against my forehead so no-one could see I was crying. In the interval, Johnny said, “What did you think of that?” “Not bad,” I said.

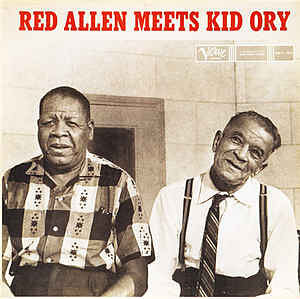

Henry ‘Red’ Allen & Kid Ory

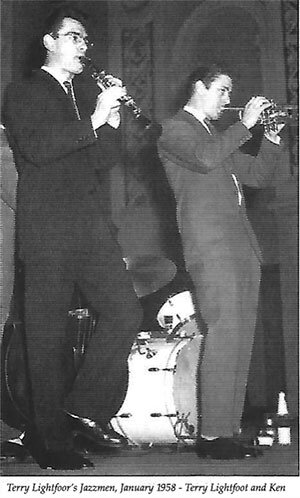

Henry ‘Red’ Allen had arrived and met up with Sonny and Brownie at Jazz Shows. He was here working with Kid Ory and his Creole Jazz Band. We were working nearly every night, but I just had to hear this band. I cannot remember how I worked it, but I did. Jack Higgins, of the Lyn Dutton Agency, gave me the details, and I was set. Band call was 8.00am outside Berners Hotel on Oxford Street, and I got there, somehow. The Kid did not travel with his band – he travelled in a Roller – a boyhood ambition perhaps. The warm-up band was the Terry Lightfoot Jazzmen which, at that time, had Alan Elsdon on trumpet.

Henry’s warm-up consisted of a series of low pressure exercises played so quietly that the high notes were almost whistled. The band was wonderful, the rhythm section was solid and relentless. Kid Ory played tailgate trombone like only he could, but Henry Red’s inventive playing dominated the band. I picked up on his showmanship, too. He made a point of playing to the people in the cheap seats behind the band, and played a lot of one-handed stuff. Years later, John Petters gave me a tape of that session. It seemed like most of the good stuff I was trying to play was Henry Red’s. It was all there on the tape, and I had only heard it once live. Back on the road with my head full of Henry Red, I was having a great time, even if what I played was not always a good fit.

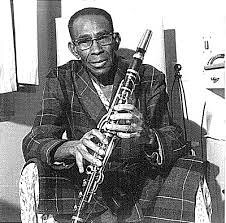

Playing with George Lewis

At one of our sessions we were told that in March we were to tour with George Lewis. I could not, no, would not, believe it. I felt that if I looked forward to it, something would go wrong, so I blocked it out of my mind until the day. Come the day, I walked into Jazz Shows, 100 Oxford Street; it was true, he was there. He was quite a small man, and frail. When he had assembled his clarinet it looked almost as big as him. There was nothing small or frail about his playing, though. He could be a powerhouse. We played Germany with the Alex Welsh Band, who had Archie Semple on clarinet. Between George, Acker and Archie, some pretty fair clarinet playing went on. George had a female minder, Dorothy Tate, whose job seemed to be to stop him enjoying himself. His cigarettes were rationed and drinking was out. It didn’t take him long to discover the whisky bottle in my cornet case. He did like a slug before he went on, to steady his nerves. George once told me how much he liked Artie Shaw’s playing and seemed genuinely surprised when I told him that I preferred his. I don’t think he ever understood why so many Europeans so loved his music. Playing with George was one of the greatest musical experiences of my life.

At one of our sessions we were told that in March we were to tour with George Lewis. I could not, no, would not, believe it. I felt that if I looked forward to it, something would go wrong, so I blocked it out of my mind until the day. Come the day, I walked into Jazz Shows, 100 Oxford Street; it was true, he was there. He was quite a small man, and frail. When he had assembled his clarinet it looked almost as big as him. There was nothing small or frail about his playing, though. He could be a powerhouse. We played Germany with the Alex Welsh Band, who had Archie Semple on clarinet. Between George, Acker and Archie, some pretty fair clarinet playing went on. George had a female minder, Dorothy Tate, whose job seemed to be to stop him enjoying himself. His cigarettes were rationed and drinking was out. It didn’t take him long to discover the whisky bottle in my cornet case. He did like a slug before he went on, to steady his nerves. George once told me how much he liked Artie Shaw’s playing and seemed genuinely surprised when I told him that I preferred his. I don’t think he ever understood why so many Europeans so loved his music. Playing with George was one of the greatest musical experiences of my life.

90% Gin!

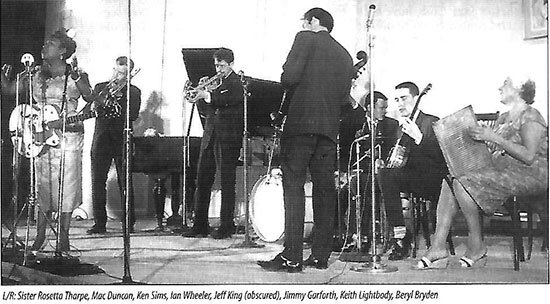

Sister Rosetta was another American singer who seemed to consider musical bar lines to be a European impediment to free expression – you just had to go with the flow ……

… At one of the shows she sang hot gospel music with Donna Hightower. Their counterpoint was fabulous and they generated enormous swing. Back stage, I got quite emotional and thirsty, and took a large swig of Sister Rosetta’s iced milk. She drank quite a lot of milk. It nearly blew my head off – it was about 90% gin!

In September we recorded the LP ‘High Spirits’ for Polydor and embarked on what was, in effect, a promotional tour, paired with the Kenny Ball Band. I really enjoyed the tour and Kenny’s trumpet playing. Our record sold well and Kenny had a hit with “Midnight In Moscow”. On New Years Eve, 1960, the band was booked to play in Manchester at the Bodega Club.

Diluted by Commercialism

By 1962, the idealism and sincerity that had fuelled the revival had been diluted by commercialism. Humph escaped into Mainstream; Cy had abandoned his followers and gone to India to commune with his god. Of the big three revivalists who played the clubs, the Guv’nor stood alone. I do not include Chris Barber in this group because Chris has always appeared to me to be the consummate professional bandleader who has always run a commercially successful jazz band, even during an era when to be called commercial was an insult to one’s musical integrity. The silver thread that identifies all his bands is, for me, his love of Traditional Jazz and the crystal clear lead provided by his trumpeter, Pat Halcox, a wonderful player.

Consider that at this time there were 140 plus jazz clubs booking professional bands, some more than once a week, I didn’t know 140 top class, professional Traditional jazz musicians, never mind 140 top class bands. The result was fairly predictable. There were some bands with just one or two good musicians in them and some with none. Bands wearing silly uniforms proliferated like fungus on a dead tree. My dreams of playing jazz for a living were turning to dust, so I went to see my agent, Lyn Dutton, at his lair in Great Chapel Street. When I got there, trombonist / bandleader Dave Keir was giving a member of the staff a frightful ear-bashing. Despite his impassioned oratory, it was plain to me that he was getting nowhere. Eventually he left, to a slamming of doors that shook the building. Silence. Colin Hogg of the agency appeared. “Come in,” he said, ushering me into his office. The situation was worse than I thought. Some of the clubs that had started in the last few years were folding, and many of the clubs still operating were paying such small fees that it was not worth the agency’s time to deal with them. He could, however, get me work in Germany.

Germany

Most of the lads in my band did not fancy working six to eight hours a night, seven nights a week in Germany. To me, it seemed preferable to doing maybe three or four gigs a week somewhere in the UK.

I found the work easy. Each set comprised of three tunes, then there was a break while the waitresses sold beer. Long John was a star. He did four sets – a skiffle set, a Kansas City Blues set, a band set, and late at night he sang and played a solo set, usually Leadbelly or Bill Broonzy stuff. On this set he would do the tables. Wherever he was in the club, you could hear him playing and singing “Goodnight Irene”, “Little Liza Jane”, “Corinne Corinna”, or, if the sugar daddies were in, “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love, Baby”, and “The Glory Move”. He was magic; that is, when he bothered to turn up. At one of our gigs, The Kaleidoscope in Essen, Albert Nicholas came and sat in with the band once a week: I presume it was his night off. I still find it hard to believe that I played with a man who played with Joe ‘King’ Oliver, Jelly Roll Morton, Louis Armstrong etc, etc.

In Dusseldorf we played at a place called the Jazz Capp. Almost opposite was a Modern jazz club, and performing in that club was the Horace Silver band. Blue Mitchell, his trumpeter, and Gene Taylor, the bassist, came over and sat-in with my band. Blue was quite at ease playing in the NO style, and Gene sang wonderful blues. I was invited over to have a blow with the Horace Silver band. It was with some trepidation that I went – I have never got into playing Modern jazz. “Don’t worry,” said Blue, “Everything we play is either a spiritual, / Got Rhythm or Panama.” He was right, and I had a ball. The respective managers of the clubs held a meeting and decided that such goings on would confuse their clients. Further musical fraternisation between Tradders and Boppers was VERBOTEN.

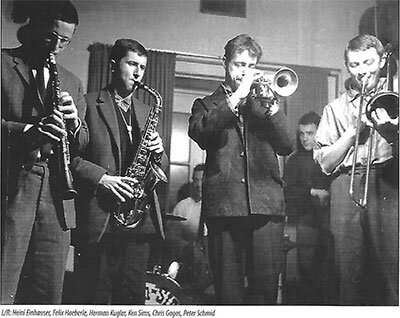

I joined Terry’s band in early May, 1964. He had Billy Law on drums, and the rest of the rhythm section were my old mates, Colin Smith (bass), Barney Bates (piano), and Wayne Chandler on banjo. The trombonist was Roy Williams, a budding genius (or was it bleeding genius?). The lad was quite barmy, schizophrenic – he was never quite sure whether he was Moriarty or Neddy Seagoon!

I joined Terry’s band in early May, 1964. He had Billy Law on drums, and the rest of the rhythm section were my old mates, Colin Smith (bass), Barney Bates (piano), and Wayne Chandler on banjo. The trombonist was Roy Williams, a budding genius (or was it bleeding genius?). The lad was quite barmy, schizophrenic – he was never quite sure whether he was Moriarty or Neddy Seagoon!

In London, The Marquee Club was somehow combining R&B and Mainstream/Modern jazz. John Baldry had recovered from his electrocution and was performing there with his Hoochie Coochie Men, featuring Rod Stewart. He was also working with a group called Blues Incorporated, which included in its ranks Mick Jagger and Charlie Watts. I played there with a band led by Barber banjoist Eddie Smith. It had Dougie Richford on clarinet, and from the Johnny Dankworth band ,Tony Russell (trombone), Spike Heatley (bass), and Ronnie Stevens (drums). It’s true, I tell you. More importantly, Buck Clayton played there with Humph’s band. He was something else, controlled but hot, melodic but rhythmic. To me he sounded like the trumpet equivalent of Ben Webster, and what a team they made. Buck was sweet on Barney’s girlfriend, but it would be hard to imagine two more apparently different men.

Shortly after, George Lewis toured with the Barry Martyn band. I caught them at The 100 Club. It was nice to see George again – what a tone he had. I saw Pee Wee Russell with the Alex Welsh band at the Crown, Morden. He did not have a beautiful tone.

Louis Armstrong

The first Louis concert was on May 30 at the Hammersmith Odeon. The band was Tyree Glenn (trombone), Eddie Shu (clarinet), Billy Kyle (piano), Danny Barcelona (drums), and George Catlett (bass). We were to do two shows per night. Our second tune, first house, was “Mood Indigo”. In the middle of the first chorus I felt Louis’ presence; I turned and glanced into the wings and there he stood, looking at me. My mouth went dry, I couldn’t play. When I did get a note out it was out of tune and had a nanny goat vibrato. Terry looked past me and said “Gerrroff!” How kind, I thought, and lurched blindly into the wings. Louis had gone. Buck Clayton, Ben Webster and, I think, Ruby Braff, were there. Talk about frying pan to fire. I opened my mouth but not a sound could I make. Buck produce a hip flask. “Have a drink,” he said. I took a large swig and returned the flask. Buck said, “Don’t worry, he does that to all of us.” … In the interval between the houses I drank in the pub next door with the likes of Buck Clayton, Jimmy Smith, Joe Turner, Ben Webster and, of course, the ubiquitous Beryl Bryden.

Louis did a TV show and we rowed our way into the rehearsals. When I say we, I mean Barney Bates, Diz Disley, Ron Mckay, me and about 2000 other musicians. The first number was to be “West End Blues”. At the first notes of the intro, the hairs on the back of my neck stood up like a porcupine’s quills. As the last notes of the intro died, a little man ran from the control room, down the aisle next to us, waving his arms. Mikes were moved, tapes were placed on the stage floor, a lot of incoherent muttering took place, and ‘jobsworth’ returned to his glass palace. Louis played another, completely different intro, the pantomime was repeated. Louis played another beautifully improvised introduction – again the idiot appeared and repeated his act of vandalism.

Louis did a TV show and we rowed our way into the rehearsals. When I say we, I mean Barney Bates, Diz Disley, Ron Mckay, me and about 2000 other musicians. The first number was to be “West End Blues”. At the first notes of the intro, the hairs on the back of my neck stood up like a porcupine’s quills. As the last notes of the intro died, a little man ran from the control room, down the aisle next to us, waving his arms. Mikes were moved, tapes were placed on the stage floor, a lot of incoherent muttering took place, and ‘jobsworth’ returned to his glass palace. Louis played another, completely different intro, the pantomime was repeated. Louis played another beautifully improvised introduction – again the idiot appeared and repeated his act of vandalism.

At this point, my observations of my friends are worth noting. Diz was laughing and rubbing his hands at each intro; Ron was bent almost double, rocking back and forth and banging his head on the seat in front; Barney, a large man, was growing even larger. Like a lot of large men, Barney was an affable man with an easy-going temperament, but there was now something alarming about him. Louis played yet another beautiful intro which again produced the arm-waving idiot. The arm-waving idiot was met halfway down the aisle by an irate Barney, who gripped him firmly round the throat and informed him that he would never hear the next intro if he didn’t bugger off. On the broadcast, Louis played his standard intro.

The End of The Revival

At Jazz Shows (The 100 Club) I saw Ruby Braff playing with the Alex Welsh Band. He seemed a bit grumpy, but he played the most inventive cornet solos you could wish to hear. I couldn’t imagine being grumpy if I could play like that. In late June, the Lightfoot band recorded a programme for the BBC called “Swinging into Summer”: Roy Williams did that gig. In early August, 65, we did a `BBC Jazz Club’ broadcast with Geoff Sowden on trombone. On that gig were the Brian Green N.O. Stompers, with Alex Revell on clarinet and Gordon Bluntly on trombone. Later that year we did the Floating Festival of Jazz; always an event; the New Palladium Show with Jimmy Tarbuck, Adam Faith and Sandie Shaw; the Prince of Wales Show for ATV, and BBC Band Beat. Around this time, banjoist Wayne Chandler left us and was replaced by Bob Campbell, and a fine young trombonist joined us who claimed that his name was Campbell Duncan McKinnon “Mc’something Mc’something Burnap”. He had more teeth than Louis Armstrong. We broadcast on Radio London and Radio Caroline, compère Pete Murray, and in March, 1966, a BBC programme called “Jazz Beat” compèred by George Melly.

The bulk of our work was still the jazz clubs, but it was becoming harder to fill them and guest stars would be booked to bolster the bill. You could hear the Alex Welsh band featuring Earl Hines or Rex Stewart, or Bud Freeman. The Bruce Turner band featuring Bill Coleman, or the Humphrey Lyttelton band featuring Buck Clayton. We got Lennie Felix and Freddy Randall; no disrespect to two very fine jazz musicians, but they didn’t have quite the same pulling power.

The gradual decline in attendance was due, I think, to the natural tendency of our audiences to settle down, marry and raise children – expensive hobbies. Those who left the scene were not replaced in sufficient numbers by the younger generation, most of whom wanted their own heroes and who, in the main, preferred the music of the young R&B singers, such as Stewart, Beck, Jagger and Lennon, etc. The best paid gigs in these years were the northern working men’s clubs. They were huge, often converted theatres or picture houses. They were packed and open seven nights a week, twice on Sundays.

A swift perusal of the contracts informed that Terry (Lightfoot) was on a very nice earner. I was earning £1,500pa, not a bad wage for the time, but not top money. On those tours, the band was doing better than that a week. Well, fair do’s – if you don’t ask you don’t get. I was a bit peeved, but not as much as I was at the end of June, 1966, when Terry had accumulated enough money to quit and buy a pub. Well, until then I thought Terry was a bit cute, but my genial host? Well, whatever, I was back on the street, skint.

Jigging About

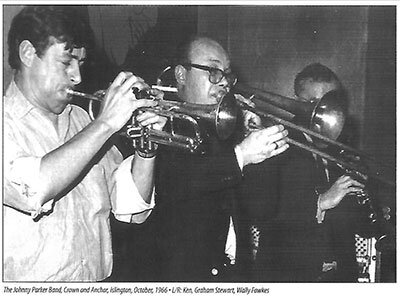

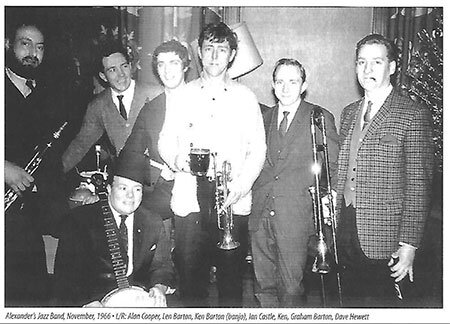

In late 1966 times were hard, and yet I was playing regularly with two good bands. The money wasn’t much, but the jazz was a bit good, at times wonderful. Alexander’s Jazz Band should have been called Barton Bros Inc. Len Barton ran the band and played bass; brother Ken played banjo and guitar and sang; brother Graham played piano. Ian Castle completed the rhythm section, on drums. The frontline was usually Alan Cooper, Forrie Cairns or Will Hastie on clarinet, Dave Hewett on trombone, and myself. The Johnny Parker band felt like home to me.

We had Chez Chesterman and myself on horns, Graham Stewart on trombone, and Wally Fawkes on clarinet. They were a dream to play with and as good as any front-line that I had ever played in. The rhythm section of Johnny Parker (piano), Geoff Kemp (bass), and Ian Castle (drums) developed a propulsive rhythmic groove, definitely left of Dixieland, according to ‘Melody Maker’ reporter, MJ. I don’t know what that means, but I did like that rhythm section.

The band had a regular Sunday lunchtime gig at the Crown and Anchor in Islington, North London, and was a favourite for sitters-in, amongst whom were trumpeters Pat Halcox, Alex Welsh and Wild Bill Davison. The ‘MM’ music critic, Max Jones, was a regular, as was Beryl Bryden. Wally’s music and gentle humour were a delight. He used to cycle to the gig – he said it kept him middle-aged. In declining an after hours drink, he said that he didn’t mind getting high, it was the burn-up on re-entry he couldn’t stand.

1967 was time to settle down. Real job, lovely wife, house, mortgage, all the bits. London house prices were out of the question, also I needed some assistance to get back into engineering, so it was back to de Pool. With a bit of help from my dad, at that time Chief Engineer, Liverpool Corporation, I got a job with the Liverpool Heating and Ventilating Co. I worked five, sometimes six days a week; in the winter months I studied engineering at night; at weekends and during the summer months I renovated the house. In between times I played my cornet.

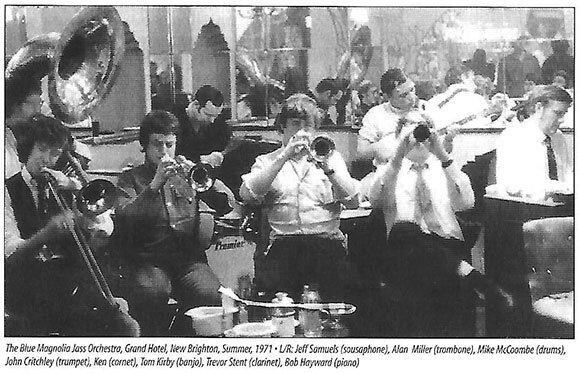

Later that year I joined the remnants of the Wallasey College of Art Jazz Band, who called themselves the Blue Magnolia Jass Orchestra. I got 7s 6d, the equivalent of 37p, for the first gig. It would be fair to say that certain technical deficiencies were evident. They did, however, develop an enormous swing. I don’t know how they did it, but they did. Well, you can learn technique. I took over leadership of the band and instigated rehearsals, and things slowly got better; sometimes we got paid more than we drank. The band had Ken Dickeson on the goddam fish horn (soprano sax), Alan Miller (trombone), Jeff Samuels (sousaphone), Geoff Walker (banjo), John Cochran (drums) and Bob Hayward (piano).

As the Mags got better, we got more gigs, got paid MONEY and recorded an E.P. entitled ‘The Blue Magnolia Jass Orchestra’ The band was John Critchley and myself on cornets, Alan ‘Red’ Miller (trombone), Trevor Stent (clarinet), Bob Hayward (piano), Geoff Walker (banjo), Jeff Samuels (sousaphone), and sleepy John Cochran (drums). Musically, the strength of the Mags was the ensemble jazz style. After about eight pints the band played with a wonderful relaxed swing. By 1970, the band had Phil Probert on banjo and Mike McCoombe on drums. This was a good band that could swing effortlessly all night. When the Gov’nor was sick, Johnny Bastable took over his band, got John (Kid) Shillito on trumpet, and hit the road. They were reviewed by Steve Voce, a critic, whose comments can destroy the bravest of egos. I take great pride in quoting from his review. “They (the Johnny Bastable band) sounded to me just like another Trad band and certainly nowhere as near to Colyer’s conception of things as the very fine Blue Magnolia Jass Band led on Merseyside by Ken Sims. Now there’s a trumpet player you should hear”.

The only review I have of the band refers to a gig we did for the Merseyside Jazz Society and calls us the Ken Sims All Stars. The rhythm section of Phil Probert (guitar), Bert Lamb (piano), Robin Tankard (bass) and Bill Williams (drums), was tremendous. The reviewer said that the music got remarkably wild at times, and he was quite right. The Mags got a regular Sunday lunch gig at the Grand Hotel in New Brighton. The gov’nor, Bill Smith, was a pretty fair jazz pianist who liked a jar and a blow, and we went from finishing at 2 o’clock to getting home at “your dinner’s in the dog” time.

In May, 1973, I received an offer from a firm of London Engineering Consultants that doubled my salary, so it had to be back to The Smoke. I must admit I left with some regret. After six years hard work, I had finally completely refurbished the house. In fact, as my train left Lime Street Station, my wife was putting up the last roll of wallpaper in the hall.

By late 74 I had renewed acquaintance with Alexander’s Jazz Band, who then had Laurie Chescoe on drums, and I was playing in some very good quartets. Chris Watford’s Elite Syncopators was one. My own band, comprising Colin Bowden (drums), Ray Smith (piano), and Gerry Turnham (clarinet), played some wonderful stuff and was augmented by trombonist Len Baldwin whenever the money was good enough.

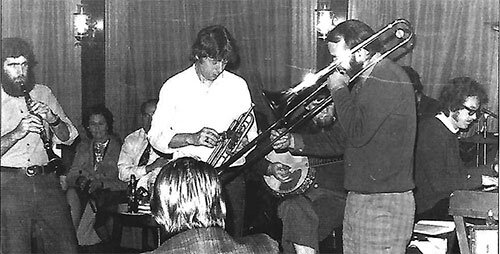

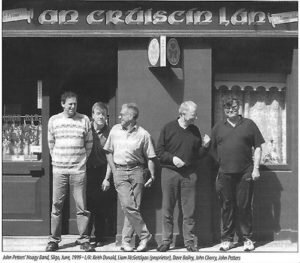

One day in ’75, the phone rang and a voice asked me to play with his band, the New Dixie Syncopators. “Ray Smith’s on piano,” it added. The gig was at a pub called the Essex Skipper, and that fine player Mac MacKay was on trombone. The drummer had a huge head of scrunched-up hair. It looked like a Cossack’s hat. Underneath was a thin, youthful face with a pencil-thin moustache. His name was John Petters. The clarinet player looked like the wild man of Borneo. A huge mop of black hair terminated just above his bushy eyebrows. A pair of brooding eyes topped a moustache and enormous beard that was almost as wide as his shoulders and which covered his upper chest. When he played it looked like a fur ball was eating the clarinet. The Cossack introduced us: “Meet Dave Bailey,” he said. John must have been impressed by Dave’s beard for he grew one just like it. The banjo player also had a beard; when Dave did a clarinet feature, they looked like the Muppet’s band. Dave also played with me in a band entitled “The Hormead Ham Fats”. We had Alan Dean on trombone and a rhythm section of Ray Smith (piano), Roy James (banjo), and Colin Bowden (drums). Wonderful! Another good band I played with, I think in 76, was Hugh Rainey’s. He had Terry Pitts on trombone, and I alternated with Tom Collins.

Guernsey

By 77, John Petters, who had told me that he was virtually unemployable, was beginning to demonstrate a talent for hustling, fixing and organisation way in excess of the abilities of most jazz musicians. As a semi-pro muso, I was unable to do all his gigs, but one I did was a fortnight in Guernsey.

In April of 81, I managed to get time off work to do a tour of Germany, and probably other places, with Max Collie’s band. He had a huge bandwagon with beds in the back with plastic covered mattresses. Heaven! Into wagon, into sleeping bag, onto bed, hand over passport, Zzzzonk. Wake up, eat, zonk. Wake up, eat, drink, play, zonk. Wake up, eat, zonk and so on. That was some band with Jim McIntosh (banjo), Trefor Williams (bass), Jack Gilbert (clarinet), and Ron McKay on drums. Ron hadn’t changed; it didn’t matter what time I woke up, middle of the night, middle of the day, he was sat up front talking at the driver.

In May, 1984, I was invited to tour the Arabian Gulf with a band called the British All Stars, which was organised by Dave Mills, the ex-Temperance Seven drummer. The money wasn’t much good but the band was, with Alan Swainston Cooper on clarinet, Mike Pointon (trombone), Ray Smith (piano), and Jim Bray on bass. Dave Mills had owed me ten bob for about 20 years. I figured that if I went I might get it back.

I managed to get Barry Palser for the tour. Barry is one of those musicians who never takes their instrument out of its case between gigs. We did ten gigs in a row. His fifth gig was twice as good as his first. By the tenth gig he was playing out of his skin and I swear he had added another octave to his working range.

The Bilk Reunion

In 1995, Phil Mason had the idea to get Acker to put together the Old Paramount Jazz Band for his festival on the Isle of Bute. Acker got Johnny Mortimer (trombone) and myself with him in the front-line, and a rhythm section of Ron McKay (drums), Tucker Finlayson (bass), Tony Pitt (banjo) and Stan Greig on piano. Some band. We flew to Scotland, and upon arrival were met by Bob Gardiner, a one-time associate of Acker. He presented us all with a bottle of whisky. Hell’s teeth, I thought. Here we go again.

On the riverboats JP had settled for a quintet, usually with Trevor Whiting on reeds. A thoughtful musician, some of the stuff he played was, well, just brilliant.

In July, 1997, John Petters’ New Orleans All Stars played the Lenk Jass Festival in Switzerland, an event made memorable by the mode of transport. We went in Barry Palser’s band wagon. Seriously under-powered, it was no match for the Swiss Alps. On the return journey there was a bang, the engine note changed and dense black smoke poured from the exhaust. It transpired that a cylinder head had collapsed. It had been eaten by the engine and spat out of the exhaust in bits. How the poor thing got us back I’ll never know. Why we weren’t stopped by the police before the engine oil caught fire, I’ll never know. We had to push her onto the boat.

Kids

As a young man, I never thought I would live past thirty; the pack of my life then – well it makes me tired to think about it. Now, here I am, seventy-six, going on sixteen, with six grandchildren. One of whom Marley, aged five, told his teacher during a focus on jazz music lesson, that his granddad played with Louis Armstrong and Acker Bilk – well, I did play on the same bill as Louis.

As a young man, I never thought I would live past thirty; the pack of my life then – well it makes me tired to think about it. Now, here I am, seventy-six, going on sixteen, with six grandchildren. One of whom Marley, aged five, told his teacher during a focus on jazz music lesson, that his granddad played with Louis Armstrong and Acker Bilk – well, I did play on the same bill as Louis.

Today’s Young Jazz Musos

The younger musicians are an eye or ear opener to me. I had trumpet lessons as a lad and played in my dad’s dance band, a brass band, and a military band. This education did not teach me much about chord progressions or how to improvise. The only advice I got, “If you can’t sing it, you can’t play it.” Your horn does not have a brain; if the sounds aren’t in your head, they ain’t coming out of the bell. The young guys just seem to appear on the scene as skilled, sometimes highly skilled, jazz musicians.

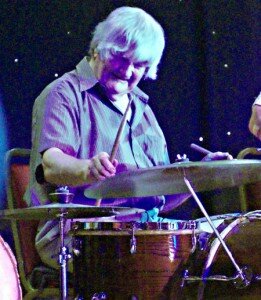

I know that they must have put a lot of hard work in; by itself, raw talent is not enough. But, playing with the likes of James Evans, Tom Kincaid, Graham Hughes, Adrian Cox, Tom Wheatley, Amy Roberts, Baby Jools, and the Linham Bros was a pleasure. Playing with fifteen-year-old Jack Cotterill, that made me feel old; I played with his dad and his granddad! All drummers, and good ones – it must run in the family.

*** *** ***

Ken Sims’ “Ramblings”

Reproduced courtesy of John Critchley, Jazz North West & Just Jazz Magazine, 2005.

Hit this link to download the full versions of the 2005 articles: Ken Sims Fred Burnet.rtfd.

These reminiscences tie in closely with my earlier Jazz&Jazz post, “Remembering Ken Sims”, featuring his star turn at Ramsgate Seaside Shuffle in July last year, one of his very last sessions. It includes my YouTube of Ken and the band playing “Tishomingo Blues”.

I want to close with his daughter Jackie’s tribute to her dad: “His engineering work is going strong in many London landmark buildings so I can’t drive through it without feeling proud… his air con/heating, plumbing, etc flows through The Barbican, Lambeth Palace… MI5 Building… many hospitals, military buildings… even the Sultan of Brunei’s Palace. He had a mathematician’s brain (couldn’t spell for toffee), I think this is why music worked so well for him. He took great pride in everything he did. If a job was worth doing…!”

Peter M Butler

Editor & Proprietor Jazz&Jazz

PS: I firmly believe in two of Humph’s mantras described in his auto-biography “It Just Occurred To Me”: “The art of life is to know when to seize on accidents and make them milestones” and “Never underestimate the power of positive eavesdropping”. Had it not been for a mix up in an accommodation booking for Ken last year, I might never have had the opportunity for my extensive one-to-one conversation with him when he shared with me so much about his life in jazz.”

My thanks go to Just Jazz and Jazz North West for making this feature possible.

Nice one. Ken was a one-off and a dream to play with.

Always loved Ken’s playing. Just listen to him and Ack on bottom of the bottle.

Hotter than Hot. Saw him at the Jazz Cap in Dusseldorf. I was there with a boys brass band so we caught him every night for 2 weeks. Great memories.

Pity he was an Evertonian

Pete Darwin MJB

I only played with Ken a few times, many years ago. It was always a pleasure.

It struck me in the opening photograph how much Ken looked like Denny Ilett, who happily is still with us,.

A fascinating article.

Cheers, Colin Wood (AB’s PJB, 1977-2013)

Chris Bateson –

I am working on a collection of memories of Soho in the 1950s/early 60s and would be very grateful to anyone who can give me any information on cornet player Chris Bateson. Who in the mid-50s, aged 17, played trumpet mouthpiece blue-blowing with Russell Quaye’s City Ramblers Skiffle Group. He was a very talented musician who seems to have vanished. He was rumoured to have played in Europe, and played pIano as well as cornet. He had a drug problem (like many more) in the 50s but came through it. Any information on Chris would be greatly appreciated. Thanks Dave Arthur

Dave, not sure but have you tried asking Hylda (City Ramblers)? She has a contact email on her website: https://hyldasims.wordpress.com/

I read this with good feelings. For years I am the biggest Acker Bilk fan. I love also the numbers he played with Ken. Now I saw there was a reunion in 1995.

The Acker Bilk Reunion band at the Isle of Bute, with the best band members Acker ever had.

Do you know if there are recordings of that concert??

It would be great if I can get those.

I hope you are able to help me.

Kind regards, Bert

Can anyone help Bert about possible recordings of the 1995 Concert?

I have just discovered that Barney Bates was the pianist on Acker Bilk’s “There’ll be some changes made” Searching for info on him I can’t find much. Is he still alive? Is there a bio somewhere? Help wd be appreciated.

I have found this, Simon, it might give you some leads to follow up:

Barney Bates, jazz pianist. In the 1960’s Barney played with Acker Bilk in his Paramount Jazz Band and, later, was often heard behind the piano in Kettners restaurant in Romilly Street.

Find this Pin and more on Soho Characters by Soho Life History.

Tags

Jazz Band

Soho

Piano

Characters

Restaurant

Street

Twist Restaurant

Figurines

Pianos

What others are saying

Barney Bates, jazz pianist. In the 1960’s Barney played with Acker Bilk in his Paramount Jazz Band and, later, was often heard behind the piano in Kettners restaurant in Romilly Street.

Ahhh, Ken.

Lovely to read about Ken and especially his views on an old fried of mine I had known for years from our days in Hull. Chez Chesterman. I vividly remember going to hear Kens band playing at he Prince of Orange, in South London I think. I was hoping to sit in for a couple of numbers. On arrival it turned out that the clarinettist was unable to get to the venue.. The consequence was that I had the most wonderful evening playing he whole gig as Ken Sims’ clarinettist! Lovely man. I regret I never heard him and Chez playing together.

Glorious, Tony! Thanks for taking the time to share such a treasured memory!